In the late 1950s and early 1960s a sea change was overtaking America’s automobile industry. Detroit had spent the decade of the 1950s catering to the exuberant marketplace by designing cars that were getting bigger and bigger, more powerful, more flashy, more heavily optioned, and just plain more heavy. The lone holdout that was producing compact economy cars consistently was American Motors, but even they had to face the fact that the game was changing.

The situation was different in Europe at that time. Recovering from a catastrophic war, European car manufacturers were producing small, light, efficient vehicles for customers that were far more concerned with the costs of operating an automobile. Plus, their market was small, making it difficult to sell enough cars at home to grow a manufacturing business. In order to survive, a variety of European manufacturers were determined to export their products to the United States to increase their sales volumes. The most widely known and most successful of these exporters was Volkswagen.

The Volkswagen was a new kind of car in the American market. It was as simple as a car could be made. Every Volkswagen had an air-cooled engine in the rear to make space utilization more efficient in the rest of the car. Air cooling also resulted in a much more simple engine and cut both operating and maintenance costs. However, the car was tiny, under powered, its styling was at least 20 years out of date, and it looked totally out of place on America’s roads and highways. Because it was a new import, a dealership network for customer support was sketchy at best. Detroit scoffed at this imported upstart and waited for it to fail. But against all odds, the Volkswagen sold like hotcakes! Its high-performance cousins, the Porsche 356 and 911, found a dedicated following as well.

As VW’s sales grew, Detroit had to respond. Chrysler created the Valiant and its cousins. Ford created the Falcon. American Motors had several small economy cars already, and was number three in sales as a result. But it was General Motors that responded with an all-new unconventional (for Detroit) car that was perhaps one of the most significant cars to ever come out of the Motor City. They built the Corvair.

The name Corvair is a combination of Corvette and Bel Air – two of GM’s most popular models at the time. The Corvair was innovative in many aspects: it was the first unibodied GM car (it had no separate frame under its body); it had a horizontally opposed, six cylinder, air cooled aluminum engine (pre-dating the Porsche 911); it had a swing axle rear suspension; and it was cleanly styled with simple lines and few chrome accents. In these respects it was similar to the Porsches. But unlike Porsche, GM offered the car in many variations including a sedan, a coupe, a convertible, a station wagon, a van, and even as a type of pickup truck. The Corvair could be ordered as a Plain Jane economy car like the VW but could also be optioned up as a more sporty car to appeal to younger buyers. But it took a Chevrolet dealer in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania to make it into a real performance car.

Donald Frank Yenko was the son of Frank Yenko, a Chevrolet dealer who loved cars and loved tinkering with them. Frank was a hard worker, and expanded the business from one dealership in Bentleyville, PA into a second one in Canonsburg. Son Don was successful, too. He was class president all four years of high school and graduated valedictorian. His interest in things mechanical ran to airplanes and flying primarily, and he was flying airplanes at 16 years old. He joined the Air Force after graduating to pursue flying. Upon leaving the service, he attended the Pennsylvania State University where he founded the school’s first flying club. He graduated when he was 30 and took over his father’s Chevy dealership in Canonsburg.

Don Yenko loved high performance cars as much as he loved airplanes. When he turned 21 and became of age to drive race cars, he developed a passion for racing. He was good at it. During his career as a driver, he raced Corvettes in everything from regional races to the 24 hours of LeMans, and from Daytona to Sebring. He was a four-time Sports Car Club of America national driving champion. He was a member of the SCCA, the IMSA, and served as president of the Corvette Club of America.

Yenko did not like losing. As things progressed in the 60s, Corvettes – Yenko’s car of choice – became heavier and heavier and were no longer competitive against new rivals, especially Carrol Shelby’s Mustang conversions. Yenko has been quoted in the June 1966 issue of Sports Car Magazine as saying “Towards the end of the 1965 season, after repeatedly looking at the rear bumper of Mark Donohue’s Mustang, I decided the only way I could stay loyal to Chevrolet was to build my own car.” So he bought a 1965 Corvair Corsa and started tuning.

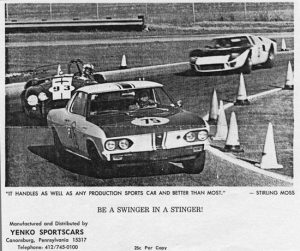

Yenko had discovered a platform on which to build a winner in SCCA’s D Production class, which was then dominated by Triumph TR4s. Chevrolet had updated the Corvair and replaced the swing axle rear end with a fully independent rear suspension, curing the Corvair’s tendency to oversteer. The Corvair Corsa had a 140 horsepower engine with four single barrel carburetors that could be built in stages up to 240 horsepower. It also could be had from the factory with a turbocharged engine rated at 180 horsepower, but Yenko chose normally aspirated engines for his purpose.

His purpose was to win races. Yenko approached SCCA to be allowed to run modified Corvair Corsas in the D Production class for the 1966 season. However, the SCCA ruled that the Corvair was not a true sports car because it had a back seat. Also, in order to be homologated, at least 100 cars had to be built to racing specification and offered for sale. To overcome these hurdles, Yenko simply removed the rear seats of his cars and committed to build 100 of them. The SCCA would eventually approve the car and its modifications, but the hurdles kept coming.

Adding to an already difficult situation, the SCCA approval did not come until the end of November 1965, and Yenko had to have all 100 cars completed by January 1, 1966! To help meet the deadline, Yenko placed a COPO fleet order (Central Office Production Order)for 100 Ermine White Corvair Corsas. This was one of the first occasions that a COPO was used to order high performance options otherwise unavailable on regular production cars. These special options included a 3.89 ratio Positraction differential and a dual circuit brake master cylinder which was normally a Cadillac part. This was the first use of a dual circuit master cylinder in a production Chevrolet.

The fact that the cars arrived at his dealership so quickly at the end of November gives an indication of the clout that Yenko had with Chevrolet. Chevrolet even gave the cars their own special serial numbers. Yenko gave them their own name as well. He called them “Yenko Stingers”.

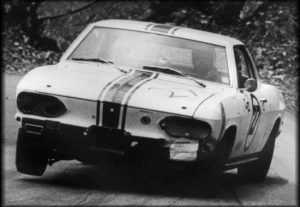

Yenko and his crew then proceeded to remanufacture these cars at his dealership, adding power upgrades to the engines, heavy duty suspension components, and improvements to the brakes and steering. They added aesthetic sail panels to all of the cars and functional aerodynamic panels to some of the cars. They also painted blue racing stripes on the white cars as required by the SCCA. The cars could be ordered with different degrees of modifications including Stage I (160 HP), Stage II (190 HP), Stage III (220 HP) and Stage IV (240 HP). In less than 30 days, the crew had finished the 100 cars, working long hours every day except Christmas. It was worth the effort. They beat the SCCA deadline, and they had a great car!

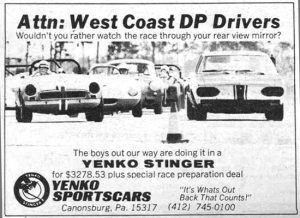

The Stingers were instantly competitive. In its very first race of the 1966 season, the Stinger finished one second behind the race-leading Triumph TR4. The combination of the light weight unibody construction, revised suspension design, and higher power engines made the Stingers formidable contestants on the track. Driver Jerry Thompson won a divisional SCCA championship in 1966 and in 1967 won the National Championship in D Production. Yenko gave Thompson the car to commemorate his winning season. The Stinger continued to compete effectively across the country. Additional, smaller batches of Stingers were built and sold to racers during the next two years, but Yenko’s attention had turned to other things – primarily the new Camaro.

Epilogue

How did Don Yenko manage to pull all this off? Not only was he successful at promoting and growing his dealership, his racing efforts created a performance halo around Chevrolet as a whole. He had proven Chevys could be champions, and the entire country took notice. This recognition enabled him to communicate directly with Chevrolet’s top brass, and that was to serve him well.

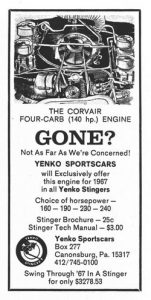

For example, in 1967 it was decided by Chevrolet to discontinue the 140 cubic inch Corvair engine altogether. This was the engine that was the basis of every Stinger powerplant, so Yenko asked Chevrolet to have the engine remain available as a COPO option for his use only. None other than Ed Cole himself, the President of General Motors, responded not only by making the engine available to Yenko but he also cut the price to help offset the cost of shipping Stingers to the west coast!

After 1966, Stinger production numbers declined dramatically making the Yenko Stinger one of the most collectible cars from the 60s. Fewer than 200 were ever built. Using the lessons learned on the Stinger program, Don Yenko went on to modify Chevelles, Camaros, and Novas into some of the fastest cars of their time and the most sought after collector cars of any era. You are indeed fortunate if you own one of these special machines!

Tragically, Don Yenko and his three passengers perished when he was landing his Cessna 210 near Charleston, WV in 1987. He was 59 years old.

For more detailed information about these special cars, visit www.copo.com.

William Hoffer, Director of Marketing, Grundy Insurance

To see a gathering of Stingers in full throat at Road America, click HERE. Tip of the hat to Dazed and Amused.